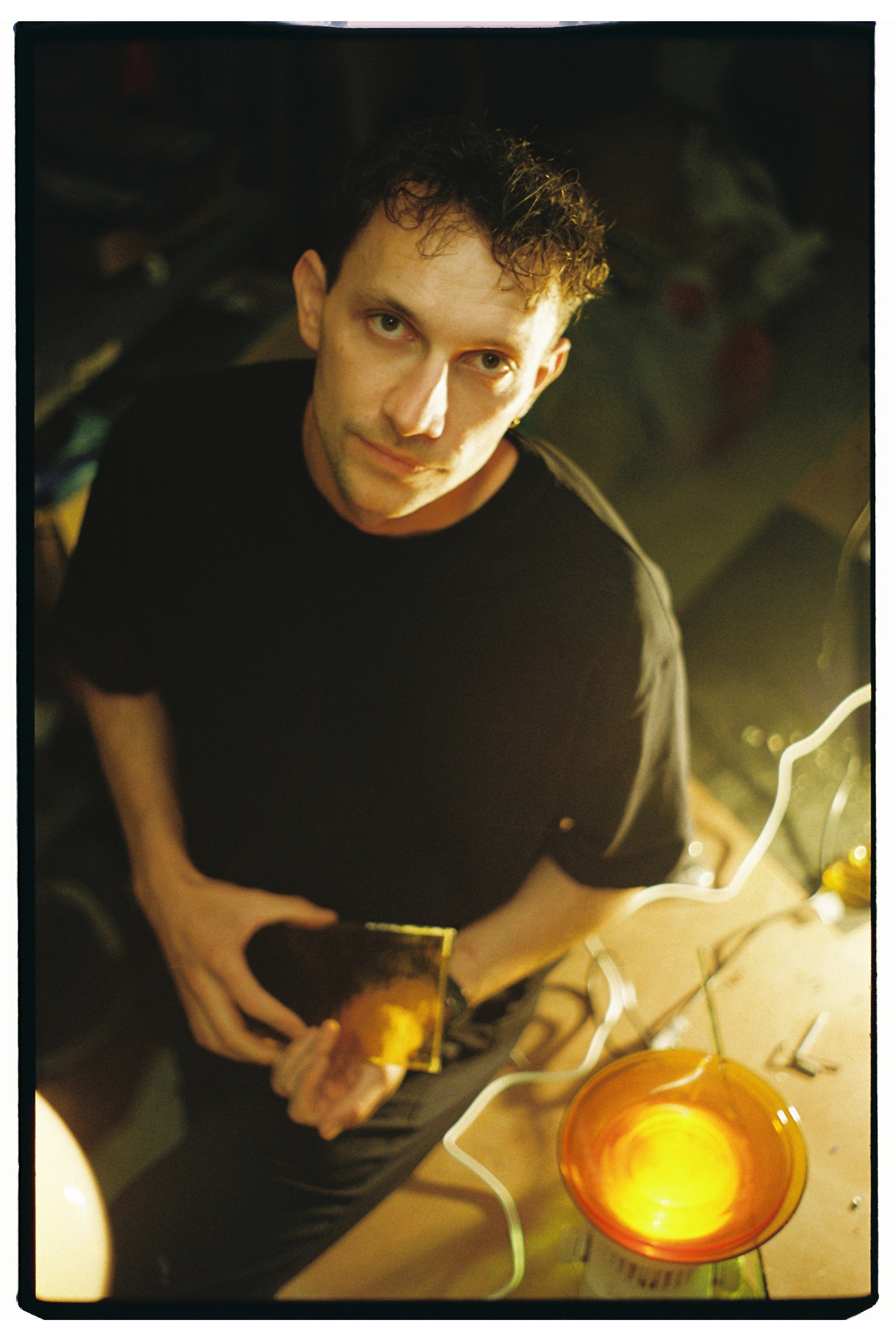

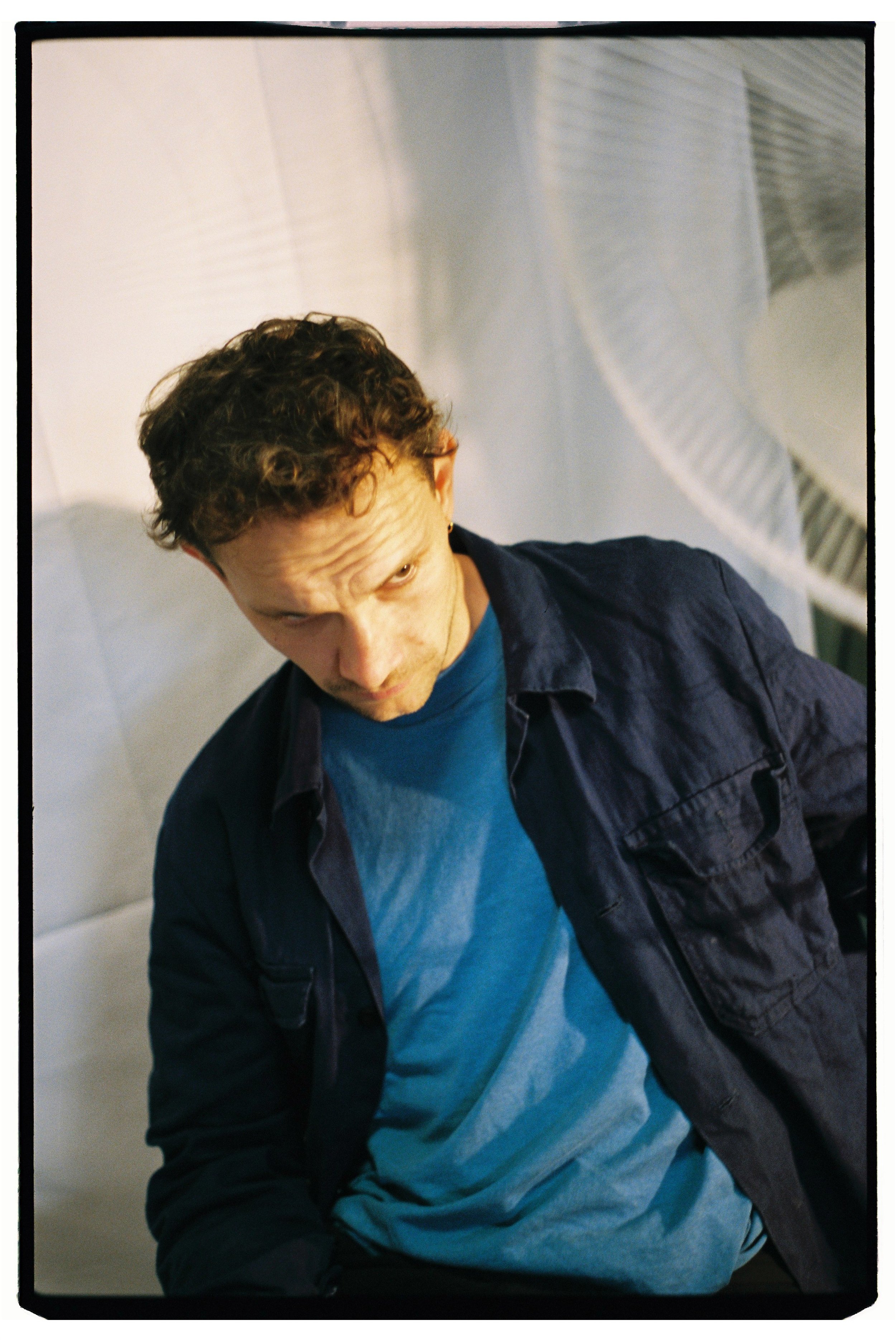

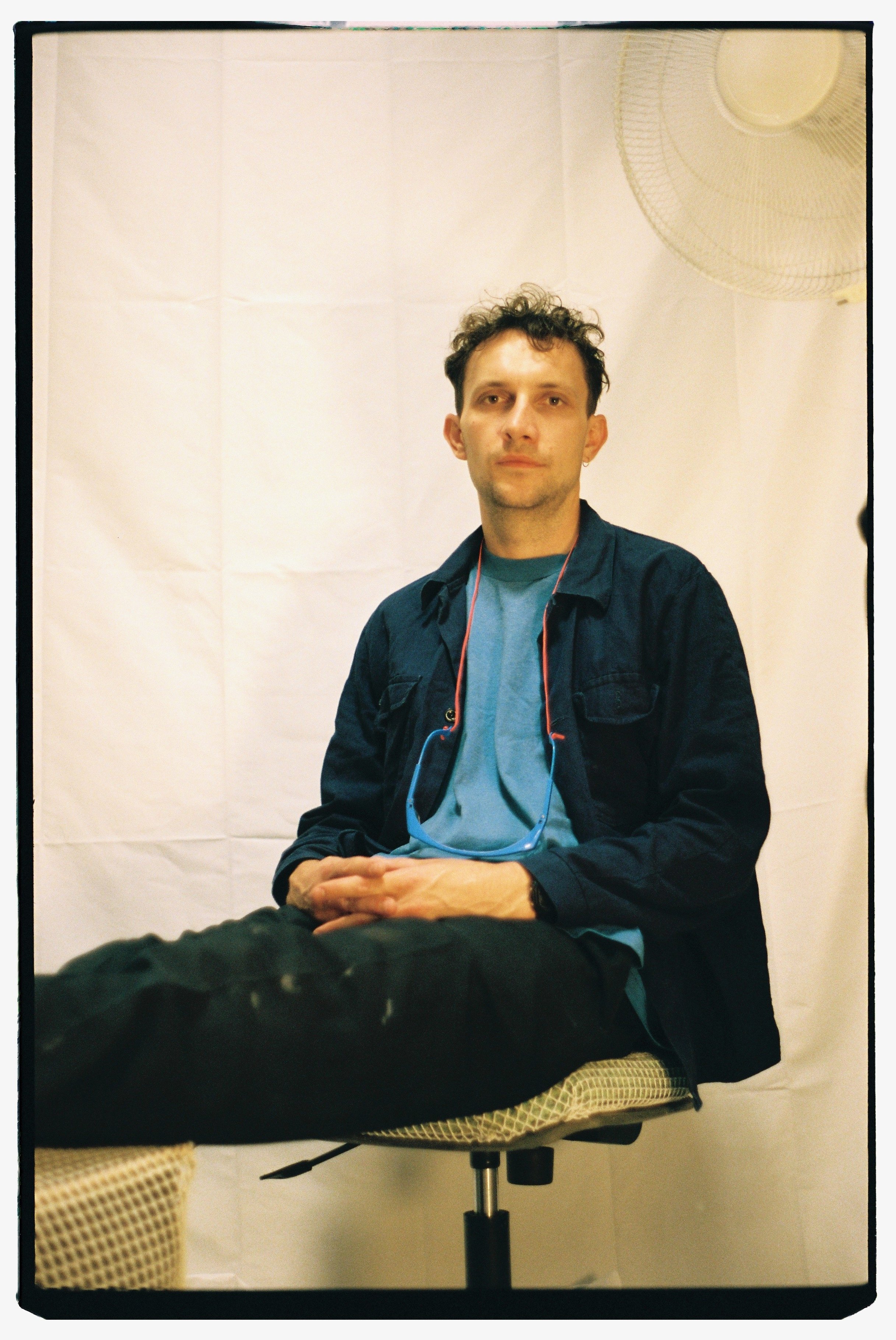

Jannis Schaefer

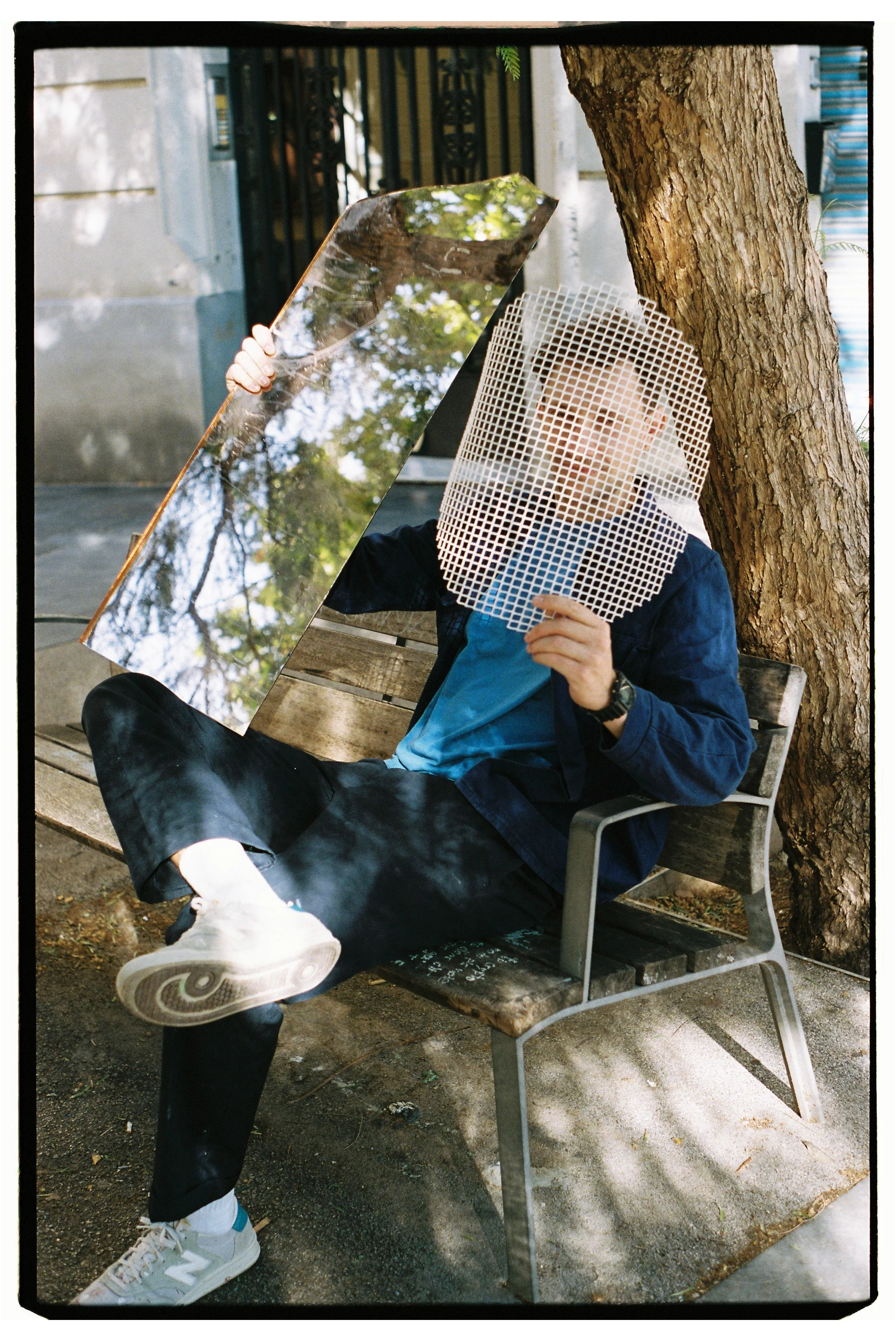

Material and graphic designer building objects with unwanted matter. Scroll down to read about the inspiration behind this shoot.

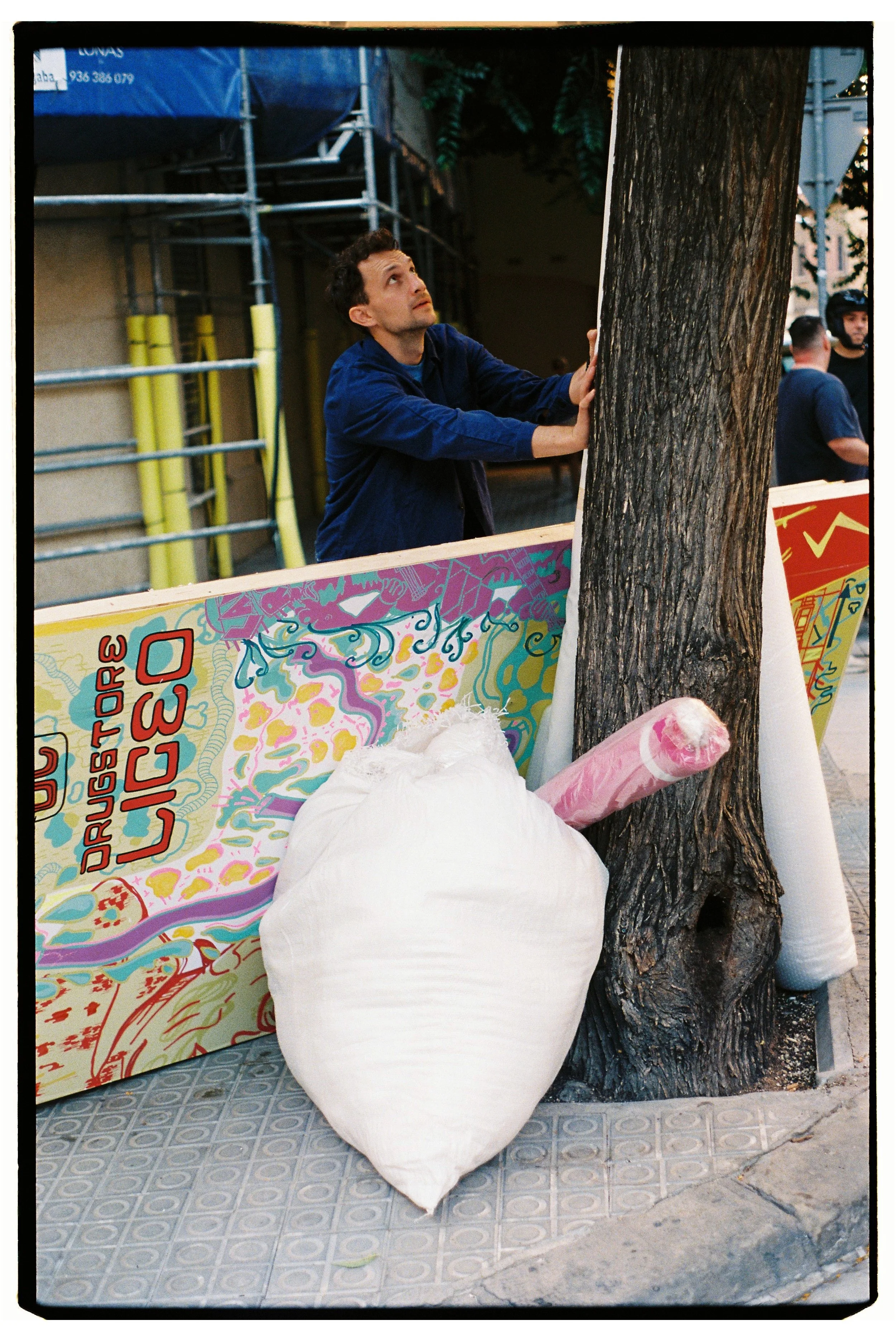

Jannis is a graphic designer from Munich, who has shifted into material design in recent years. He’s currently in Barcelona working on a project entitled Derivatives. As he describes it “Derivatives is a series of designed objects deriving from unwanted matter, urban finds, residue, and object fragments.” As we shot these photos, we got chatting about the ideas that gave birth to the project, and here I’ll try to recount some of the bits that stuck with me.

Jannis has this very German characteristic of speaking softly but with deliberate certainty. He told me of his frustration with graphic design, “You’re at the end of a massive production process, just polishing things up. You have no say in the actual product.” So he went back to the root and studied material design, and got into all sorts of experiments testing the limits of different biomaterials like potato starch. He explains we often go off track with good intentions. As we endeavour to eliminate one enemy ingredient or material, we end up with a more convoluted chain of production and new damaging byproducts to consider.

Today, I find him navigating a new path. His investigation is led by a curiosity to look at our daily environment with new eyes and undo our assumed relation to the objects around us.

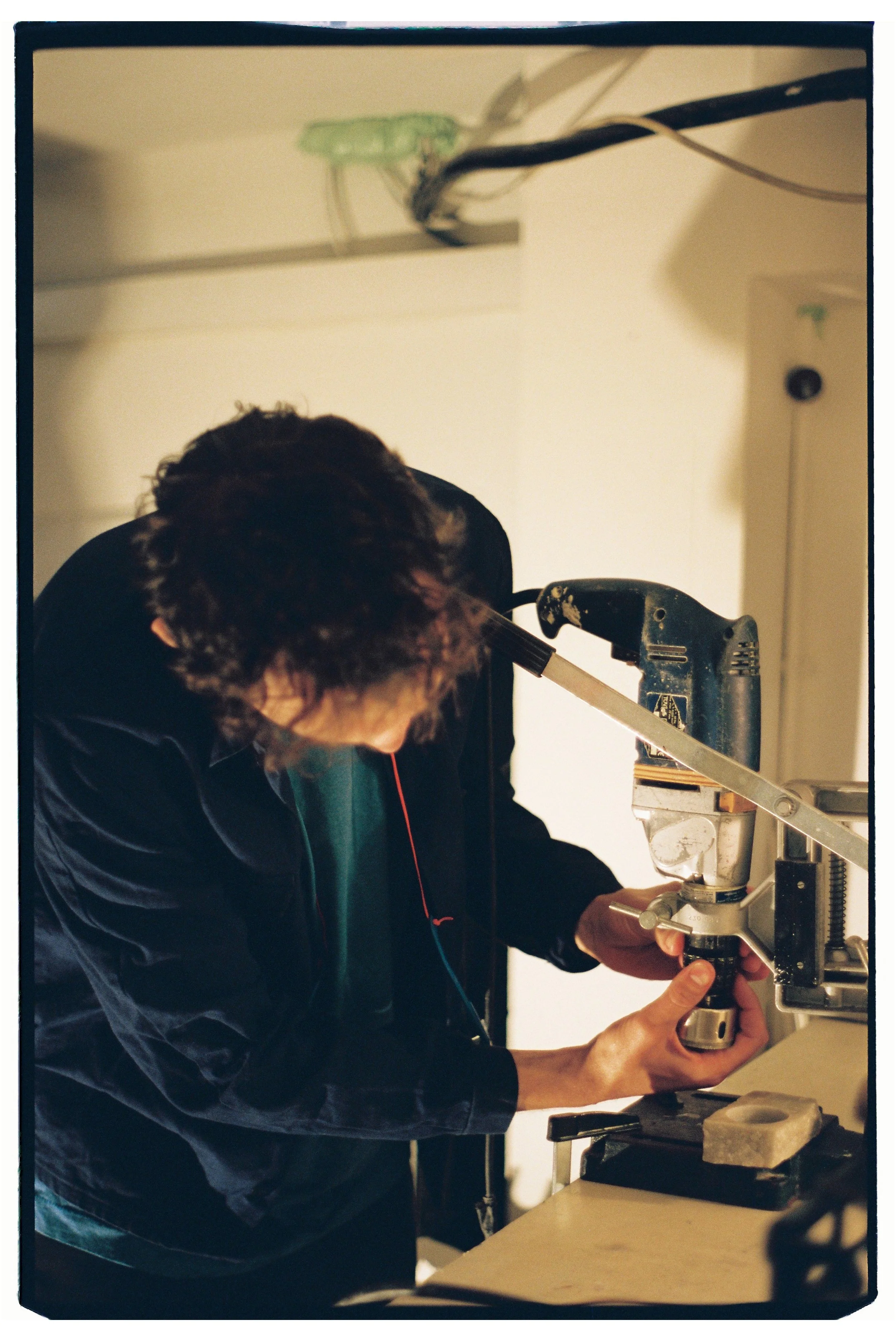

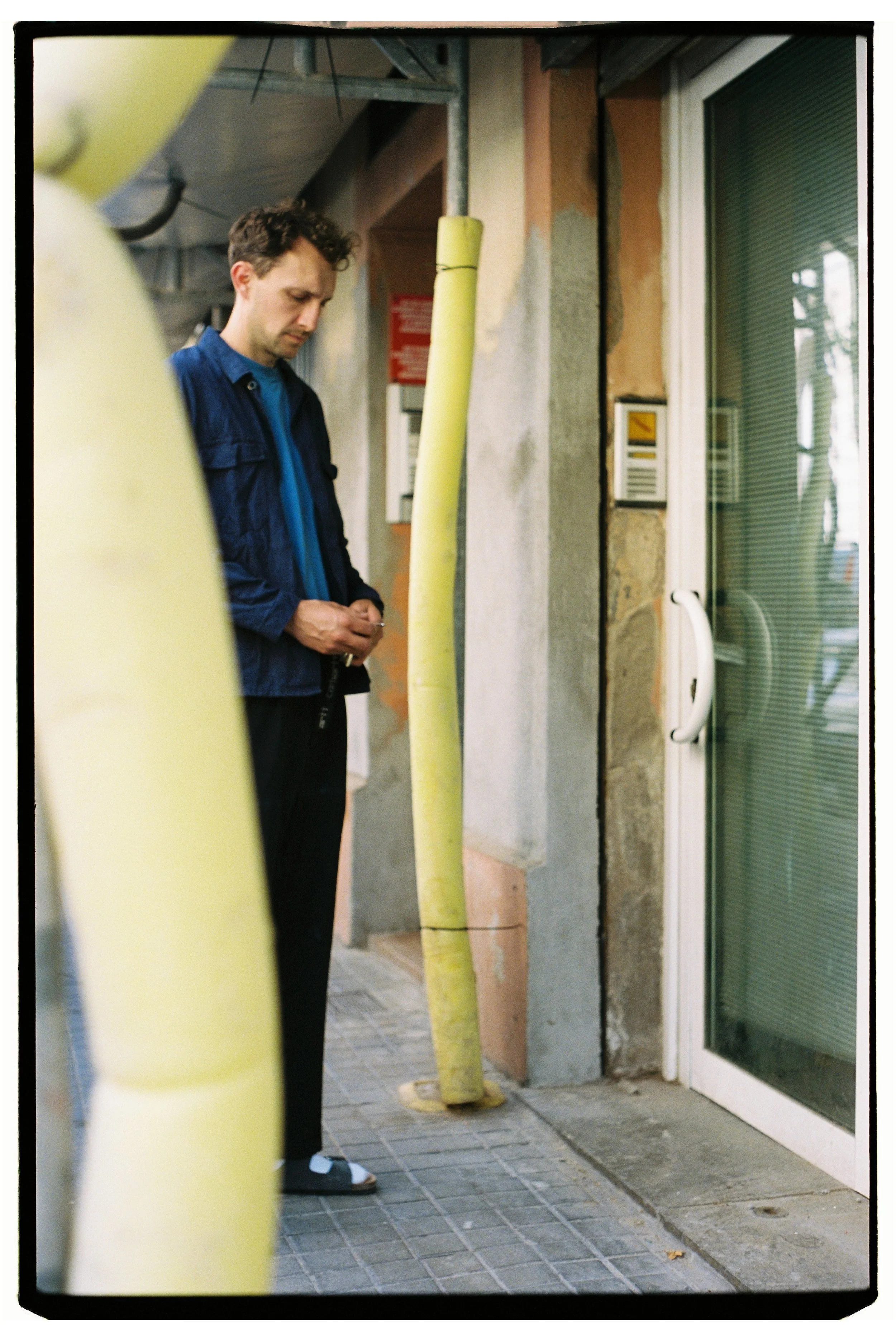

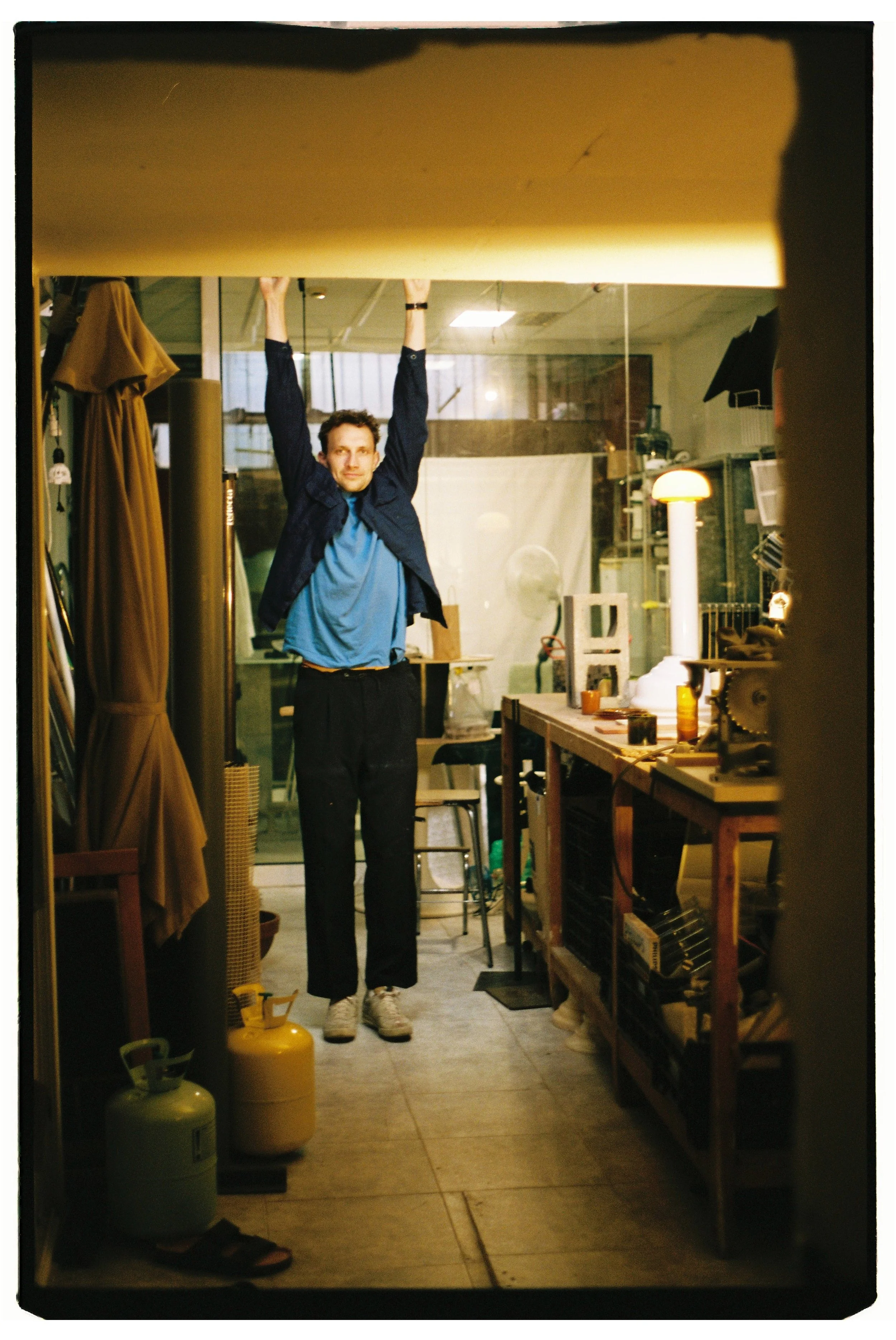

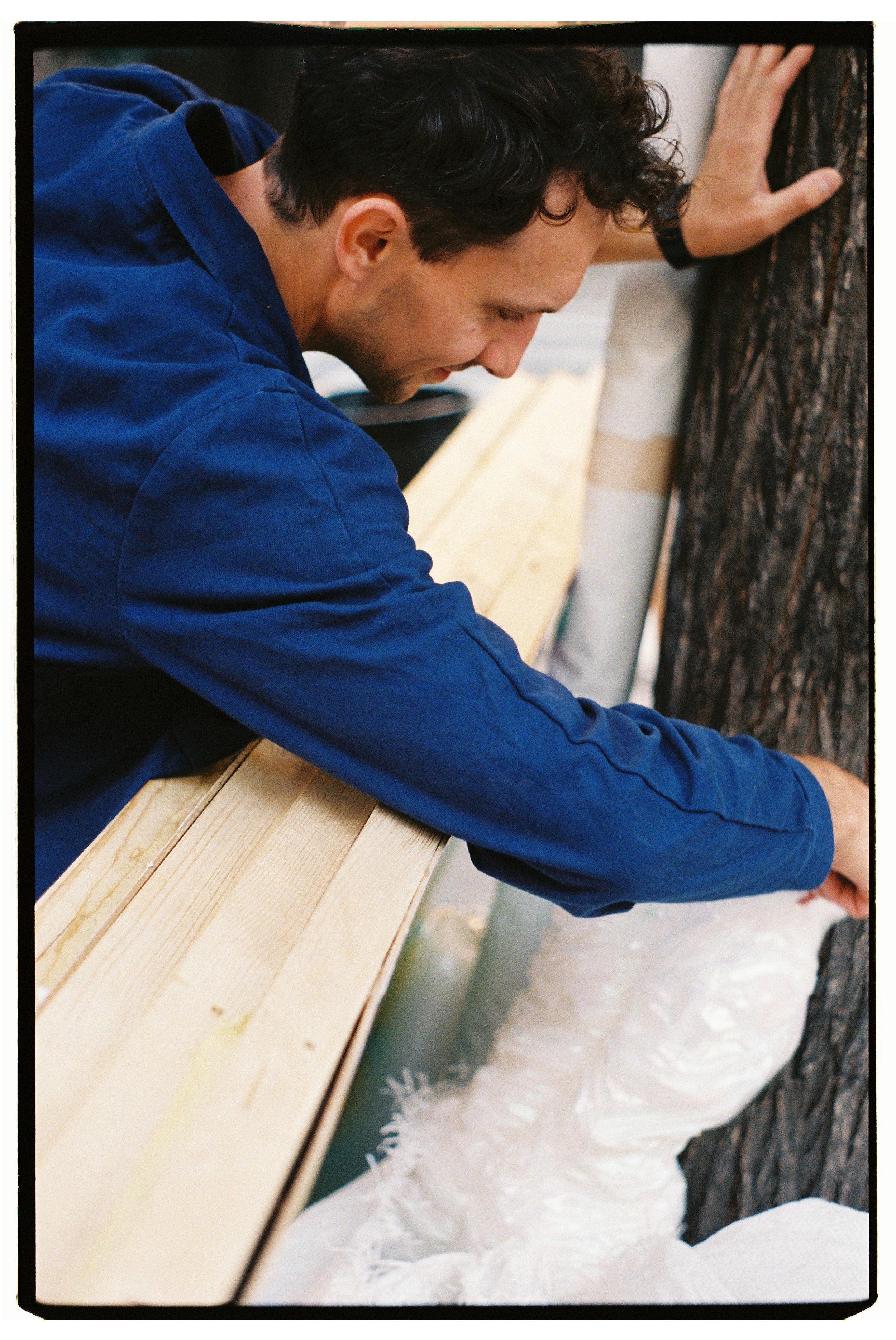

When I arrived at his studio in Poble Sec the door was open. Artist’s spaces always fascinate me because you can see how they’ve become part of the process. In photographing them, you get to trace the story of the objects made within.

If you turn left from here and climb a steep hill you reach Montjuïc, a sprawling park on the hillside. Walk down a few blocks in the opposite direction and you´ll hit Parallel, one of the city’s busiest roads. The neighbourhood feels sleepy and frantic at the same time, squeezed between nature and the city centre. The transition is abrupt and makes a rather poetic setting for an ecological designer.

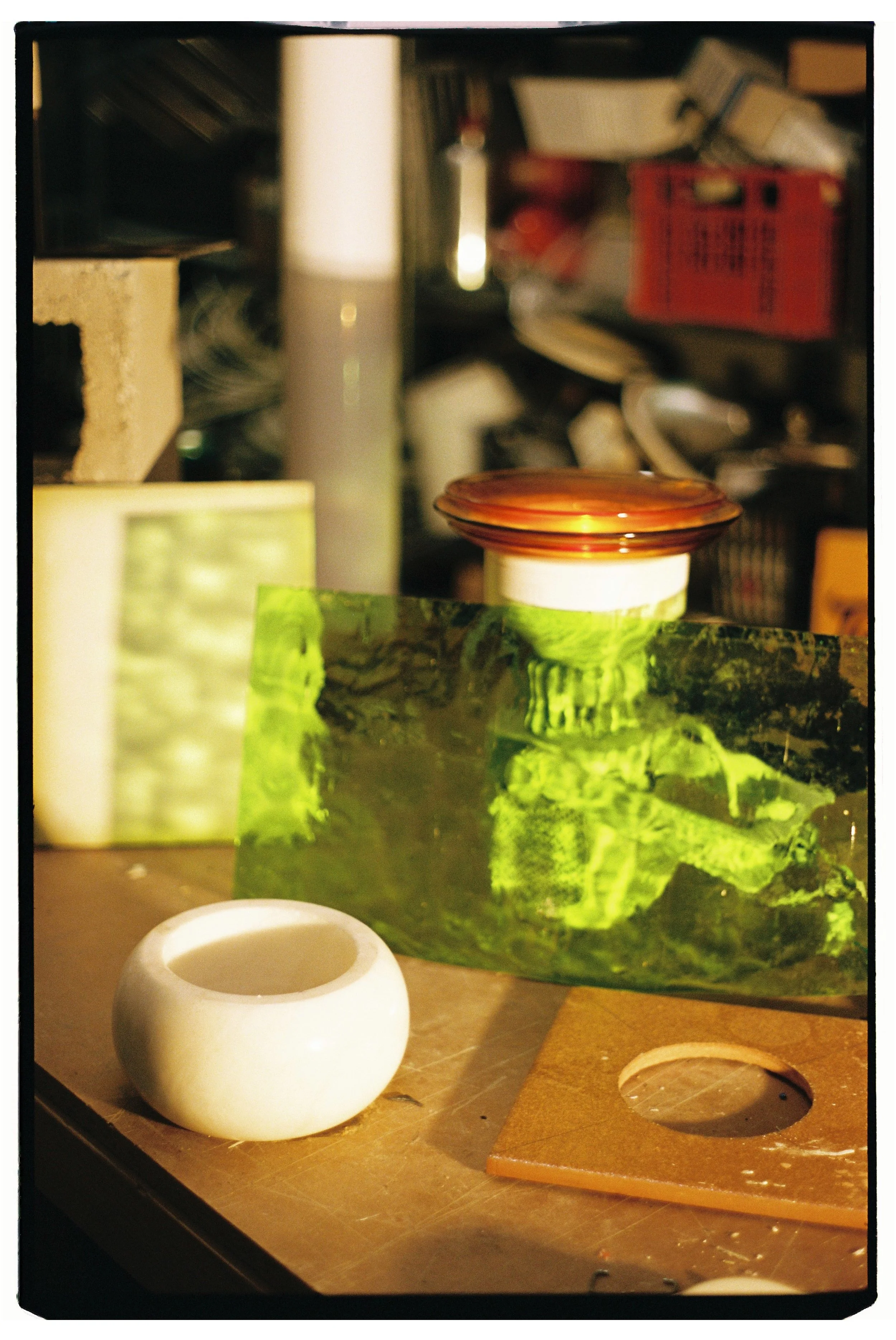

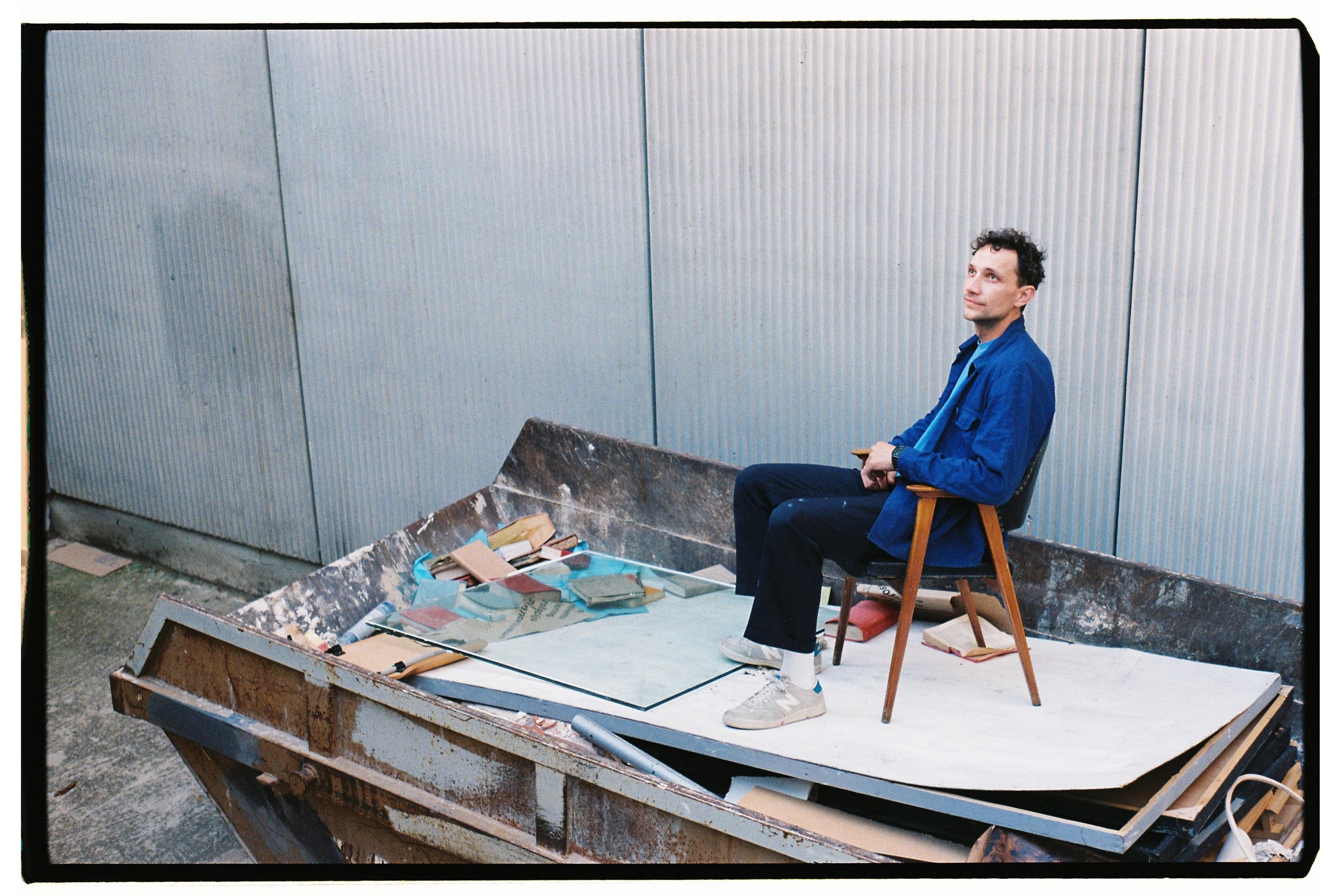

Stepping inside, the building is long and narrow. Every inch of wall space is precariously stacked with unidentifiable materials, and random objects like safe boxes, sheets of glass, bits of piping, and wound up cables that are heaped in the corners.

Jannis was introduced to the owner after calling a phone number he found taped to a lamppost outside. Here they stored keys to properties all over the city when it was the office of a failing security company. By the time Jannis got here it was mostly piles of old letters and invoices, which he eventually reduced to a pulp and turned into business cards. So goes the lifecycle of a locale.

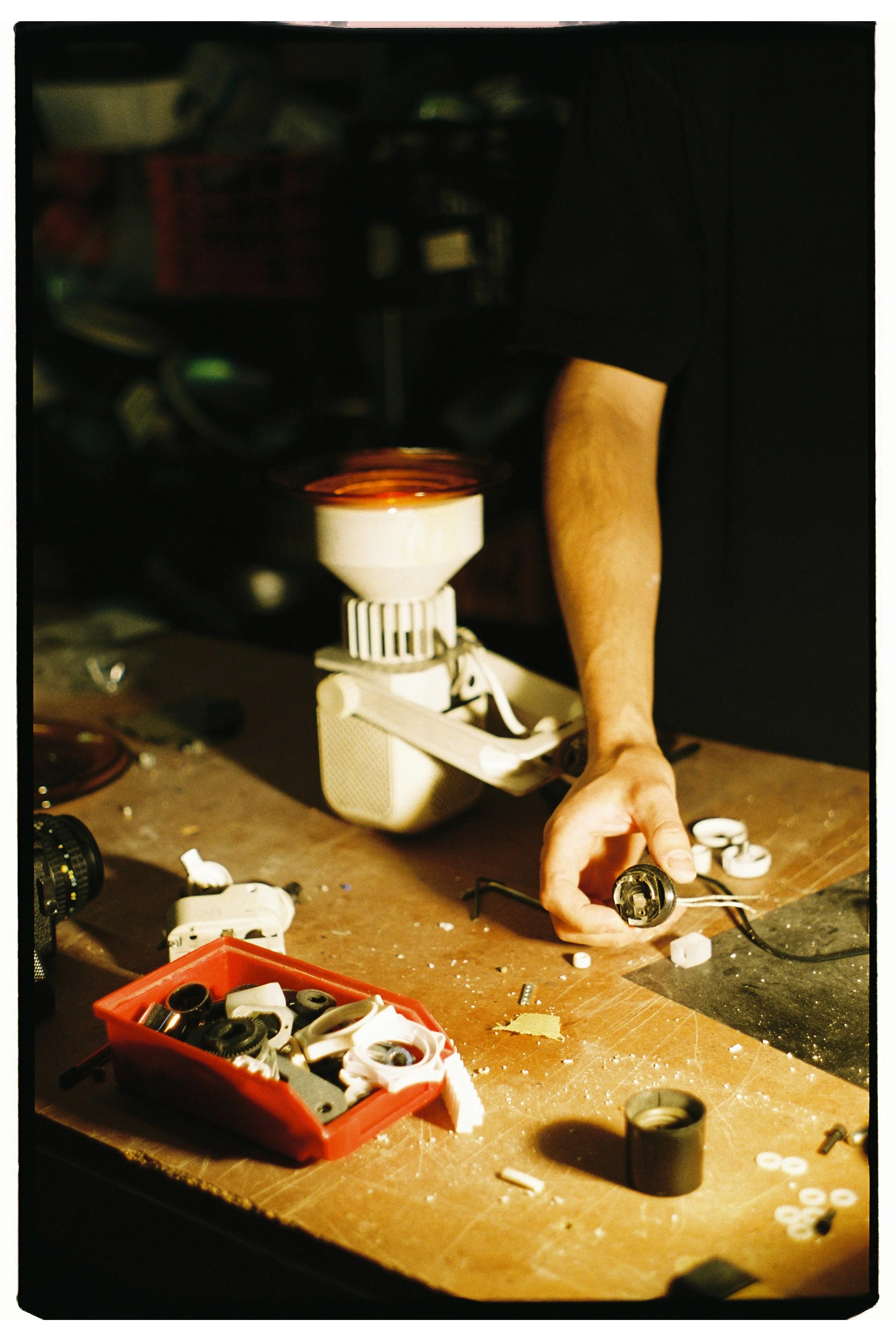

In this space, he crafts functional objects from found materials. Although functional is a strong word in design, I would argue that any object which was perceived as trash, and is now desirable is highly functional.

To separate beauty from function is to disregard millions of years of evolution.

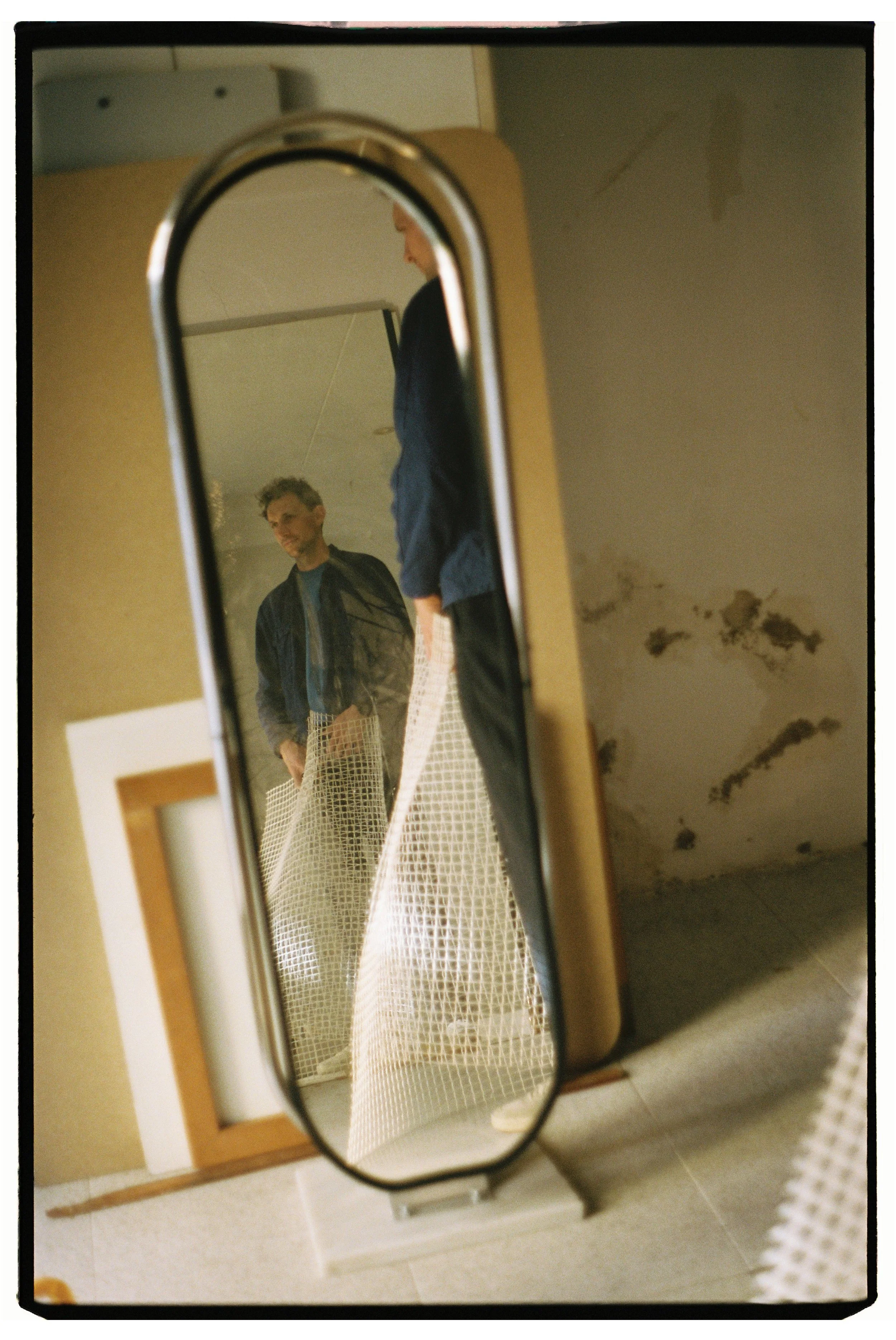

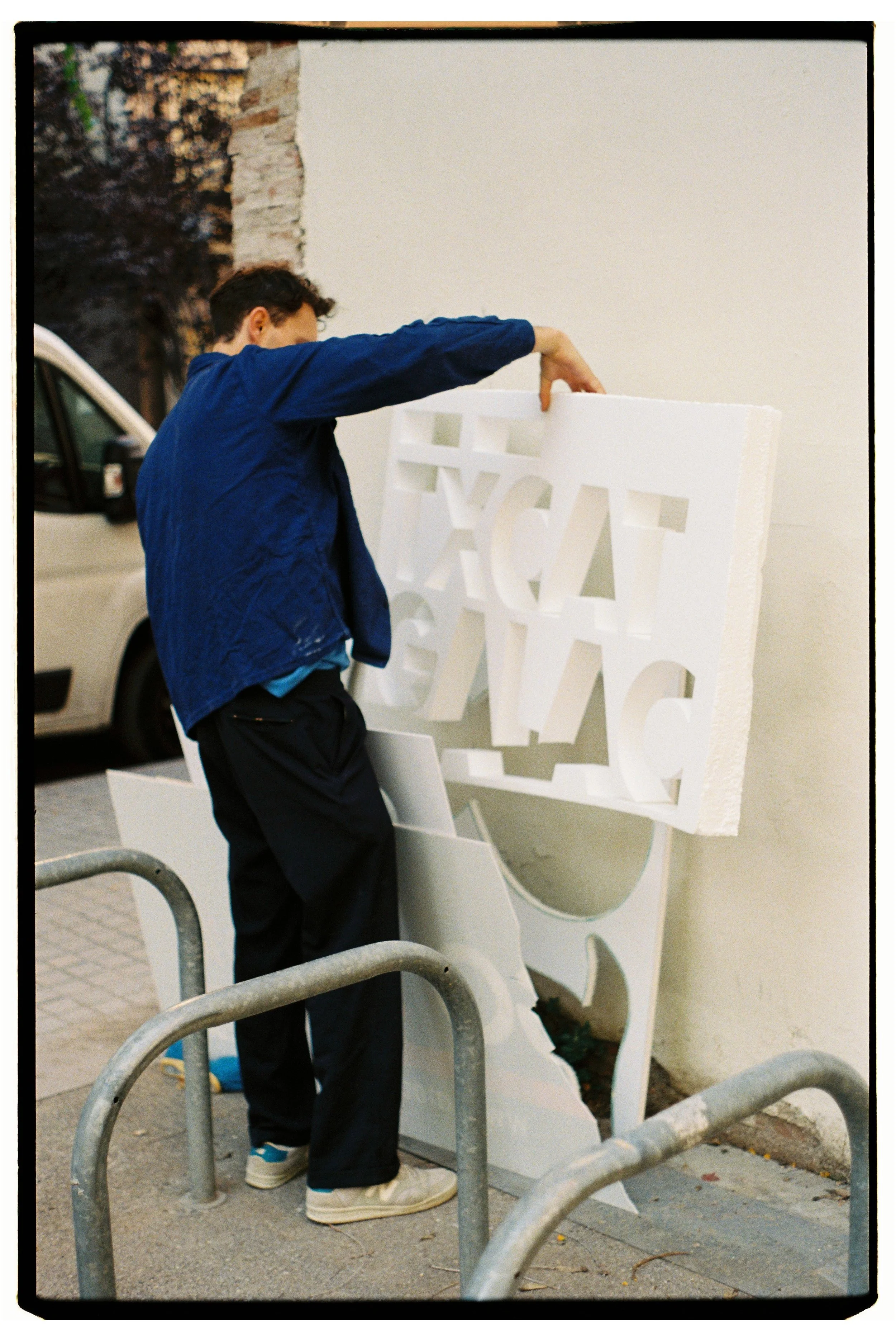

Jannis’ creative approach applies nature’s patient cyclical design to a wasteful urban environment. The foraged objects around us don’t particularly need a name. In this space they are more material than thing. More function than form. What they have been, or will become doesn’t change their usefulness in the present context.

As soon as we name an object we restrict its function, and it is much more easily discarded.

In the 1890’s, architect Louis Sullivan famously stated that “form follows function”, inspired by nature’s evolution into shapes that perfectly fit their roles within ecosystems. Today, however, one of the most urgent lessons we have yet to learn from nature is that there is no such thing as waste.

Waste is a convenient term we have invented for things we can’t find a use for.

Through Derivatives, Jannis is taking this observation as creative fuel to explore the potential in the materials all around us under the principle that “form follows material.”

We can all look to nature’s fundamental truths to tilt our perspective of a dense city, where the amount of inputs to be processed is dizzying and life moves too fast to question. The urbanite cannot possibly engage with all the stimulus, so they switch lenses to focus. We search for specifics. We run errands. Trying to avoid interruptions, and purchase solutions.

Instead of looking at sustainable design as a to-do list of problems to be solved, Jannis takes a critical approach to our hyper-specialised lifestyle. The consistency in his work comes out of a total change in perception, seeing every object as a co-creation with the material.

It is a more natural approach because it returns to the human intuition that brought us here — thinking creatively with the material we have available. Imagining that a fallen tree could become a shelter, that a rock could become a knife. These basic steps were key to our evolution as a species, but this way of seeing is somewhat anti-social in a supermarket.

We are no longer obliged to consider an object as the result of a process. We simply replace old things with new things that have the same name, but with an extra adjective stuck on the front.

In Jannis’ work I am happily reminded that more choice is not the solution to excess.

It illustrates that by intentionally limiting our resources, we may even cultivate a richer, more meaningful existence. It challenges the assumption that abundance leads to fulfilment, revealing instead how an overload of options can render us passive participants in our own lives, overlooking the connection we have with our environment, and the ability we have to change it.